101. Design & Zen Summary I

SUBSCRIBE TO UNMIND:

RSS FEED | APPLE PODCASTS | GOOGLE PODCASTS | SPOTIFY

Both solve a problem —

though of differing import.

Zen’s is the broadest.

In the last session of live dharma dialog online at the Zen center — transcribed as the last podcast in the series on the most recent spate of mass shootings — the last participant worried that meditation would not help children in the classroom, owing to the complexity of the many personal and social issues they are confronting. Not least, the elephant in every public American classroom these days, the threat of yet another school shooter. The exchange went as follows:

But don’t give up! You’re creative.

No I won’t give up. Thanks very much for your teaching.

So I mean to encourage you similarly. No matter how bad it gets, don’t give up on your zazen practice. And be creative in your personal life and approach to problem-solving. I closed the last by stating that this concludes the dharma dialog that took place on this occasion. But the dialog continues. In the next four sections we will draw some interim conclusions as a kind of summary of Zen and Design thinking, or those aspects of this intersection discussed to date, namely the Four Noble Truths, the first teaching of Buddha, and the Four Spheres of influence and Endeavor, my attempt at a comprehensive model of the real world in which we live and practice Zen.

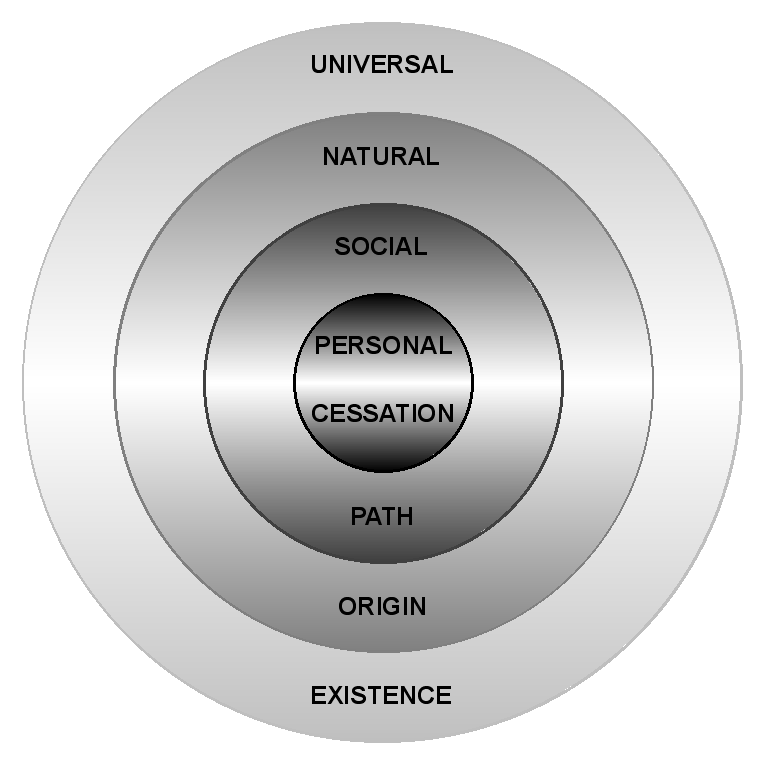

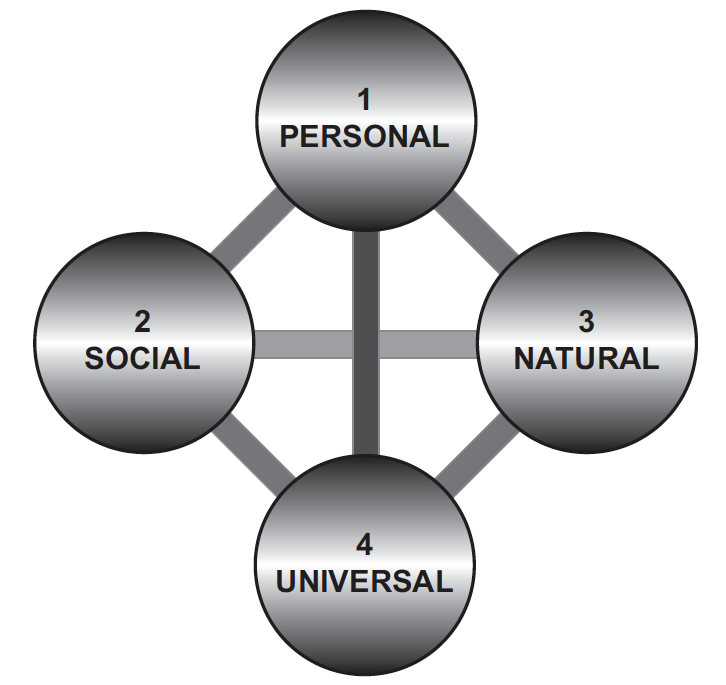

Buddha’s First Sermon, alternatively called “Setting in Motion the Wheel of the Law,” “The Middle Way,” or “The Four Noble Truths,” lays out his description of the reality that all sentient beings face, and his prescription for what action to take to deal with it, namely the Noble Eightfold Path. We will include my semantic models of these teachings, along with my configuration of the Four Spheres in which we live and practice — the Personal, Social, Natural, and the Universal. Hopefully we can draw some correlations between the two models to get a better vision of how our Zen life can proceed in the context of the current complexities of the world. The illustration below shows that my model of nesting spheres can be usefully associated with both quartets.

Before going into specifics of the four truths and their interconnectedness with the four nested spheres of our existence, it seems pertinent to ask the question: Why four? Why not five, or three, or six, eight, or twelve? I believe it has to do with what R. Buckminster Fuller developed and taught in his design science and geodesic geometry developments. The fourth point closes the system.

Interestingly, if not coincidentally, Sokei-an, the Rinzai priest who accompanied Soen Shaku on his trip to America to introduce Zen Buddhism to the West at a world convocation of religions toward the end of the 19th century, said something similar about the relationship of Buddhism to Christianity. Paraphrasing broadly, he commented something to the effect that Buddha appeared some 2500 years ago and counting, propounding a kind of compassion and wisdom that required the surrender of the self. 500 years or so later, Christ appeared, preaching a kind of divine love that “closed the teaching.” In other words, the two great religious systems are complementary, not competitive.

If we recall the many other teachings that are expressed in sets of four, there are the four fundamental elements of tradition: earth, wind, fire, and water. The four logical propositions, or tetralemma of ancient pedigree: it is; it is not; it both is and is not; it neither is nor is not. Then there are the four seasons: spring, summer, fall and winter. In a more contemporary context there are the four fundamental forces of the universe: gravity, electromagnetism, and the weak and strong nuclear forces, potentially with a fifth or more lurking in the shadows of dark matter and dark energy. Modern biology posits four forces of evolution: mutation, genetic drift, gene flow, and natural selection. The seemingly impossible phenomenon of an airplane in flight is also explained by four forces: lift, thrust, drag and weight. Orville and Wilbur must have figured that one out.

Setting aside for now the apparent contradiction that in each of these cases, we can find other qualified candidates for inclusion, such as space and consciousness, sometimes listed with the other four elements, remember that Fuller was positing the simplest model of any given system, which by definition has an inside and an outside. The tetrahedron is the first geometric shape to fill the bill. But it is deceptively simple in appearance. When we look at the connecting tissue between the four points, we see that there are six such, and each can be interpreted as cutting both ways, resulting in twelve aspects of interconnectedness between the four points. (See illustration if you cannot visualize for yourself.)

Not coincidentally, this number, 12, the familiar “dozen” from the Latin duodecim, pops up regularly here and there in the vernacular, in all sorts of categories of information: twelve lunar cycles or months of the solar year; the visible spectrum or color wheel; the hours of the day (in Master Dogen’s day, doubled to 24 in modern times), and not to forget the twelve apostles as an outlier, with Jesus making a baker’s dozen. You may counter that there are only three primary colors: red, blue, and yellow, in terms of pigment. But the hues that we can distinguish separately tend to fall into twelve combinations of the three primaries, the secondaries of violet, orange and green, and the tertiaries of red-violet and red-orange, blue-violet (or purple) and blue-green, yellow-orange and yellow-green, closing the circle. And then there is the Twelvefold Chain of Interdependent Origination, Buddhism’s summary model of how things get to be the way they are, through life cycles of rebirth, aging sickness and death that are the lot of all sentient beings. Most importantly of course, those of the human persuasion.

We can point to many groupings of less than four, such as the Three Treasures of Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Or the three legs of the Zen stool articulated by John Daido Loori: faith, doubt, and perseverance. Or the Three Times, past future and present. For each of these triads, I would submit that the fourth point is YOU. You complete the tetrad, the four-pointed system, in your relation to the other three. Buddhism is like that. It included the observer from the very beginning. Buddha was a human being, and had no interest in expounding a theory of existence that did not include human beings as observers. The whole point of his teaching is the nature of reality and our place in it.

Other teachings such as the Noble Eightfold Path can be parsed into a tripartite grouping: Right Wisdom (view and thought or understanding and intention); Right Ethics or Conduct (Speech, Action and Livelihood); and Right Discipline (Effort, Mindfulness and Meditation) again with the caveat that the English term “right” is a limiting translation for the intended meaning. Buddha’s “right” is more a verb than an adjective, taking action to right our raft, sailing on the seas of Samsara. Again, the fourth component completing this model is, dear seeker, yourself.

While these enumerations may appear to be arbitrary, they do seem to function as memory aids, mnemonics, as well as revealing an underlying need and yearning for order, in conceiving a model of our existence, which can seem so chaotic and arbitrary in its manifestations. We can be forgiven a bit of conjecture in our efforts to explain the unexplainable and conceive of the inconceivable. As long as we are willing to return to the cushion, and contemplate our creative grasp of reality, I say: No harm, no foul. The monkey mind has some utility, if limited, in adapting to and embracing reality, warts and all.

In the next session we will return to consideration of the quartets of Noble Truths and nesting spheres. We will look at each of the pairs of correlates in order: Universal Existence — of sufffering, that is — Natural Origin, Social Path, and Personal Cessation, of dukkha. Stay tuned.

Zenkai Taiun Michael Elliston

Elliston Roshi is guiding teacher of the Atlanta Soto Zen Center and abbot of the Silent Thunder Order. He is also a gallery-represented fine artist expressing his Zen through visual poetry, or “music to the eyes.”

UnMind is a production of the Atlanta Soto Zen Center in Atlanta, Georgia and the Silent Thunder Order. You can support these teachings by PayPal to donate@STorder.org. Gassho.

Producer: Kyōsaku Jon Mitchell